The Global Brain Drain: How Skilled Visa and Migration Policies Impact Developing Nations

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the global brain drain, examining how skilled visa and migration policies impact developing nations. By drawing on research from the World Bank, the OECD, and studies from institutions like the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), this paper moves beyond a superficial understanding to present a data-driven exploration of the topic. It dissects the primary “push” factors, such as economic instability, inadequate infrastructure, and political turmoil in developing countries, and contrasts them with the powerful “pull” factors of developed nations, including lucrative skilled visa programs and superior living standards. The analysis quantifies the devastating economic and social costs for developing nations, citing a US $303.4 billion productivity loss in a case study on Pakistan. While acknowledging the detrimental effects, the article also offers a nuanced perspective by exploring the concepts of “brain gain” and “brain circulation,” highlighting the positive impacts of remittances and diaspora networks. Finally, it proposes a dual-pronged approach to mitigation, suggesting that developing nations invest in human capital and governance while urging developed countries to adopt more ethical recruitment and collaborative capacity-building policies.

Just In Time (JIT) production is a revolutionary approach to manufacturing that has transformed efficiency in various industries. At its core, JIT is centered around the idea of producing only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the exact quantities required, thereby minimizing waste and streamlining operations. This production methodology shifts the focus from mass production to a demand-driven system, reducing excess inventory, optimizing resource usage, and improving overall product quality. The JIT philosophy goes beyond simple production scheduling; it embodies principles such as continuous improvement (Kaizen) and waste elimination to create a lean and efficient manufacturing system. In this article, we will delve into the fundamental aspects of a just in time production, explore its key principles, and examine how it reshapes the way manufacturers approach efficiency and productivity in modern industries.

Keywords: brain drain developing countries, countries with the most brain drain, braindrain, visa, talent, literacy, migration, immigration consultant, global migration, skilled visa, international organisation for migration, immigration visas, undocumented immigrant.

1. Introduction

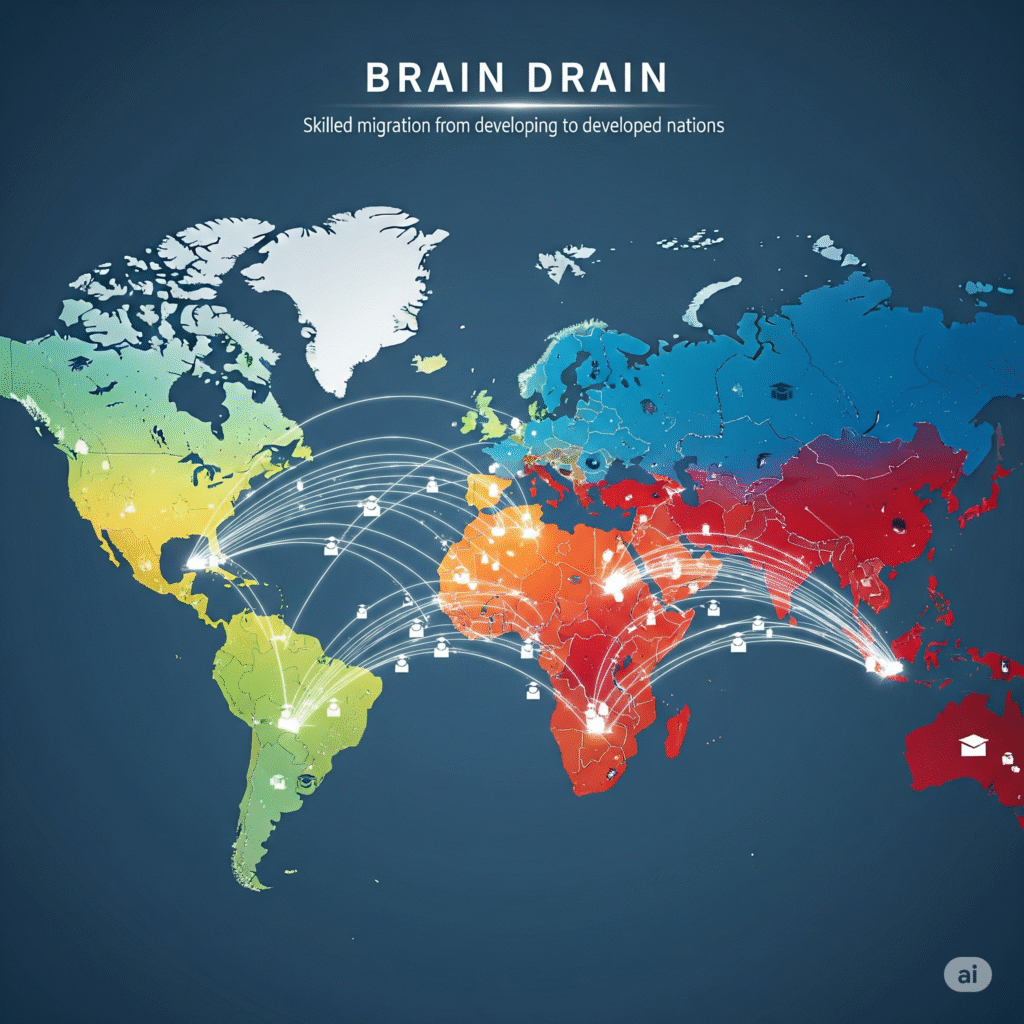

The brain drain, a term first coined in the 1960s to describe the emigration of British scientists to the United States and Canada, has evolved into one of the most pressing socio-economic issues facing the developing world. It refers to the large-scale departure of highly skilled, educated, and talented individuals from their home countries to more developed nations. This phenomenon is not merely an inconvenience; it represents a significant and often devastating loss of human capital, which is the engine of a nation’s growth and development. This article will expand upon the foundational understanding of brain drain, utilizing detailed data from research papers, international organizations, and policy documents to present a comprehensive, multi-faceted view of its causes, consequences, and potential solutions. We will explore the complex interplay of skilled visa policies in developed countries, the systemic issues in developing nations, and the nuanced economic and social impacts on both sides of the migration equation.

1. The Push and Pull of Global Migration: A Data-Driven Perspective

The decision for a professional to leave their home country is rarely a simple one. It is often the result of a powerful combination of “push” factors in their home country and “pull” factors in the destination country. While the initial article touched on these, a deeper dive into the data reveals the stark disparities that drive this global movement.

2. Push Factors in Developing Nations

For many developing countries, the internal environment can be a breeding ground for professional disillusionment. A 2024 survey by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) found that a staggering 37% of Pakistanis want to leave the country, with educated individuals expressing a higher inclination to emigrate than their less-educated counterparts. The primary reasons cited in this and other studies are:

2.1. Economic Disincentives:

Non-competitive wages, high unemployment rates among graduates, and a lack of economic opportunities are major drivers. According to PIDE’s research, the graduate unemployment rate in Pakistan is 16%, compared to a 5% overall unemployment rate, highlighting the specific challenges faced by the educated workforce. This wage differential is a critical push factor, as skilled workers can earn several times more for the same job in a developed country.

2.2. Political and Social Instability:

Political turmoil, corruption, and a lack of a stable legal and social order create an environment of uncertainty. A study on intellectual brain drain in Pakistan found that 33% of emigrants cited political instability and threats to their lives as a main factor for their departure. This is a common theme in many nations experiencing internal conflict or political unrest.

2.3. Inadequate Infrastructure and Professional Environment:

Limited resources for research and development, substandard healthcare facilities, and a lack of modern infrastructure often stifle professional growth. A study published by the World Bank in 2010 found that the lack of opportunities for further studies and professional development was a significant driving factor for skilled workers leaving their home countries.

2.4. “Brain Waste” at Home:

The phenomenon of “brain waste,” where highly skilled professionals are underemployed or forced to take jobs below their qualification level, is a major push factor. When a doctor or engineer cannot find a suitable job, their skills and training are devalued, making emigration a logical choice.

3. Pull Factors in Developed Nations

In contrast, developed countries actively attract this talent through well-structured and enticing policies. The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), in its analysis of the economic impact of migration, has extensively documented these pull factors:

3.1. Skilled Visa Programs:

Countries like Canada, the United States, and Australia have sophisticated points-based skilled visa systems designed to attract individuals with specific, in-demand skills. These programs, such as Canada’s Express Entry system or the U.S. H-1B visa, offer clear pathways to permanent residency and citizenship, making them incredibly appealing.

3.2. Higher Standard of Living and Economic Prospects:

The promise of a better life, including higher salaries, superior healthcare, quality education for children, and a stable political environment, is a powerful lure. The OECD notes that a skilled migrant’s contribution to the host country’s public finances is often positive, as they tend to pay more in taxes than they consume in social benefits, creating a virtuous cycle of talent attraction.

3.3. Opportunities for Professional Growth:

Developed nations often invest heavily in research and innovation, providing skilled professionals with access to state-of-the-art facilities, funding, and collaboration opportunities that may not exist in their home countries. This environment fosters a sense of professional fulfillment and a clear path for career advancement.

3.4. Social and Personal Freedom:

For many, the move is also about personal freedom and the opportunity to live in a more tolerant and inclusive society. Social policies that protect individual rights and provide a higher quality of life for families are a significant part of the attraction.

4. The Devastating Impact on Developing Nations

While the initial article highlighted the consequences of brain drain, recent research provides more specific, quantifiable evidence of the damage. The loss of human capital is not just a theoretical problem; it has measurable and long-lasting effects on a nation’s economy and social fabric.

5. Economic Costs and Productivity Loss

The economic cost of brain drain can be calculated not only by the direct loss of individuals but also by the lost productivity they would have generated. A 2024 study by Khan and Ahmad of the PIDE on Pakistan’s brain drain estimated the country’s productivity loss in 2023 at a staggering US $303.4 billion. This calculation takes into account the migrants’ contribution to the global GDP, minus the remittances they send back. This demonstrates that while remittances are a significant benefit, they often do not fully compensate for the total economic output lost.

6. Strain on Essential Services

The departure of professionals in critical fields such as healthcare and education creates severe shortages that directly affect the well-being of the remaining population. A study from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (PMC) detailed the brain drain of healthcare professionals from Pakistan from 1971 to 2022, revealing that over 50,000 healthcare professionals, including more than 31,000 doctors, had emigrated. The loss of these professionals cripples public health systems, particularly in rural areas, leading to reduced access to quality healthcare and a decline in national health indicators. Similarly, the departure of qualified teachers and academics weakens the education system, perpetuating a cycle of low literacy rates and a poorly skilled future workforce.

7. Hindered Innovation and Entrepreneurship

A vibrant economy is built on a foundation of innovation and entrepreneurship. The emigration of talented individuals who would have otherwise been the innovators and job creators in their home countries stifles this growth. The absence of a critical mass of creative thinkers and skilled professionals makes it difficult for a country to develop new technologies, attract foreign direct investment, and establish competitive industries. This can lock a nation into a state of economic dependence on other countries and prevent it from moving up the global value chain.

8. The Brain Gain and Brain Circulation: A More Nuanced View

While the term “brain drain” suggests an unequivocal loss, modern research has introduced the concepts of “brain gain” and “brain circulation” to offer a more nuanced perspective. This newer perspective acknowledges that migration can also bring benefits to the home country.

9. The Role of Remittances

Remittances, the money sent home by migrants, are a major source of foreign currency for many developing nations. The World Bank has published numerous reports highlighting the importance of remittances, noting that they often surpass official development aid in volume. These funds are used for a variety of purposes, including education, healthcare, and starting small businesses, thus indirectly contributing to economic development. A study in the Economic Annals-XXI journal confirmed a strong correlation between remittances and GDP per capita growth in countries like India, Nigeria, and the Philippines, which are highly dependent on this income.

10. Knowledge Spillovers and Diaspora Networks

Skilled emigrants often maintain strong ties with their home countries, creating “diaspora networks.” These networks can facilitate the transfer of knowledge, skills, and even technology. For example, a doctor trained in the U.S. might partner with a hospital in his home country to establish new medical practices. A tech professional in Silicon Valley might invest in a start-up back home. This “brain circulation” and the resulting knowledge spillover can boost the productivity and innovation of the origin country, partially offsetting the initial loss. The ILO (International Labour Organization) has argued that the feedback effects of skilled migration can often outweigh the negative impacts, provided that countries have the right policies to harness these benefits.

11. Policy Recommendations: Mitigating Brain Drain and Promoting Brain Gain

Effectively addressing the brain drain requires a two-pronged approach: improving conditions in the countries of origin while also encouraging a more ethical and mutually beneficial approach from destination countries. Research and policy documents offer several key recommendations:

11.1. Policies for Developing Nations

11.1.1. Investment in Human Capital:

Governments must invest more in their education and research sectors, providing a stimulating environment for skilled professionals. This includes offering competitive salaries, funding for research, and access to modern technology. A study on policy recommendations for handling brain drains suggests that providing tax exemptions for research and development can attract corporate attention and incentivize innovation, helping to retain qualified personnel.

11.1.2.Improving Governance and Economic Environment:

Creating a stable political climate, a robust legal system, and a favorable business environment is crucial. This includes reducing corruption, ensuring job security, and promoting a culture of meritocracy.

11.1.3. Engaging the Diaspora:

Actively engaging with expatriates can be a powerful tool. Policies could include incentives for return migration, investment schemes that channel diaspora remittances into productive ventures, and programs that facilitate knowledge-sharing between the diaspora and professionals at home.

11.1.4. Targeted Sectoral Support:

Focusing on critical sectors like healthcare and education is essential. Governments can offer special incentives and improved working conditions to professionals in these fields to retain them. As one study on African healthcare systems recommended, public-private partnerships can be utilized to improve infrastructure and provide better compensation for medical staff.

11.2. Policies for Developed Nations

11.2.1. Ethical Recruitment:

Developed nations, particularly those with a high demand for healthcare professionals, should consider the ethical implications of their recruitment policies. The World Health Organization (WHO) has a Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, which encourages countries to limit active recruitment from developing nations facing critical shortages.

11.2.2. Collaborative Partnerships:

Instead of simply absorbing talent, developed countries can partner with developing nations to build capacity. This could involve funding training programs, establishing joint research projects, and facilitating a temporary “brain circulation” where professionals can work abroad for a time and then return home with new skills and knowledge.

12. Conclusion

The brain drain is a complex and deeply rooted issue with profound consequences for developing countries. While the data paints a stark picture of lost human capital and economic stagnation, a closer look also reveals opportunities for “brain gain” through remittances and diaspora networks. . Understanding this dynamic is the first step toward effective policy-making. Combating this phenomenon requires a comprehensive strategy that addresses the systemic push factors in developing nations while encouraging a more ethical and collaborative approach from the developed world. By investing in their own people, improving governance, and actively engaging with their diaspora, developing countries can work to turn the tide and transform a potential “drain” into a “gain,” fostering a future of sustainable growth and prosperity.

References

- Khan, J., & Ahmad, N. (2024). The economic cost to Pakistan for the talent lost because of brain drain. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE).

- Sajjad, N. (2011). Causes and Solutions to Intellectual Brain Drain in Pakistan. The Dialogue, 6(1), 32-55. Qurtuba University. https://www.qurtuba.edu.pk/thedialogue/The%20Dialogue/6_1/Dialogue_January_March2011_31-55.pdf

- The World Bank. (2023). Module 9—Brain Drain. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2023/brief/module-9-brain-drain

- OECD. Economic impact of migration. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/economic-impact-of-migration.html

- Aleyomi, M. B. (2025). Possible solution to mitigate the effect of brain drain. Caribbean News Global. https://caribbeannewsglobal.com/possible-solution-to-mitigate-the-effect-of-brain-drain/

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (n.d.). Migration of highly skilled persons from developing countries: impact and policy responses. https://www.ilo.org/media/304546/download

- Memon, A. G., & Khan, H. N. (2023). Brain drain of healthcare professionals from Pakistan from 1971 to 2022: Evidence-based analysis. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10364271/

- Tufan, H., & Cakir, M. (2022). Policy Recommendations for Handling Brain Drains to Provide Sustainability in Emerging Economies. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/23/16244

- Investopedia. (2025). Understanding Brain Drain: Causes, Effects, and Global Examples. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/brain_drain.asp